The Season That Asks Too Much

Reading Time: 4min

By the second week of December, the world begins to instruct you on how to feel. Streets are strung with lights that have never learned kindness. Supermarkets play music insisting on joy while you are counting coins. Greetings—“Merry Christmas!”—are hurled at you like assumptions. Somewhere in the middle of it all, there is an expectation, unspoken but firm, that whatever grief you carry must wait its turn until January. Christmas is not just a holiday. It is a performance.

You are expected to arrive smiling, grateful, healed—or at least convincingly pretending. Depression, society whispers, can take a break. Loneliness must make space for togetherness. Grief, if it exists at all, should be tasteful, quiet, brief.

But grief does not follow calendars. Depression does not answer fairy lights. Loneliness does not vanish because there are people near.

For many Kenyans, Christmas does not amplify joy; it amplifies absence. Empty chairs become louder in Nairobi townhouses, in Kisumu homesteads, in Mombasa apartments. Silence becomes deliberate. Memories return sharpened by ritual: this is where they used to sit. This is how it used to be.

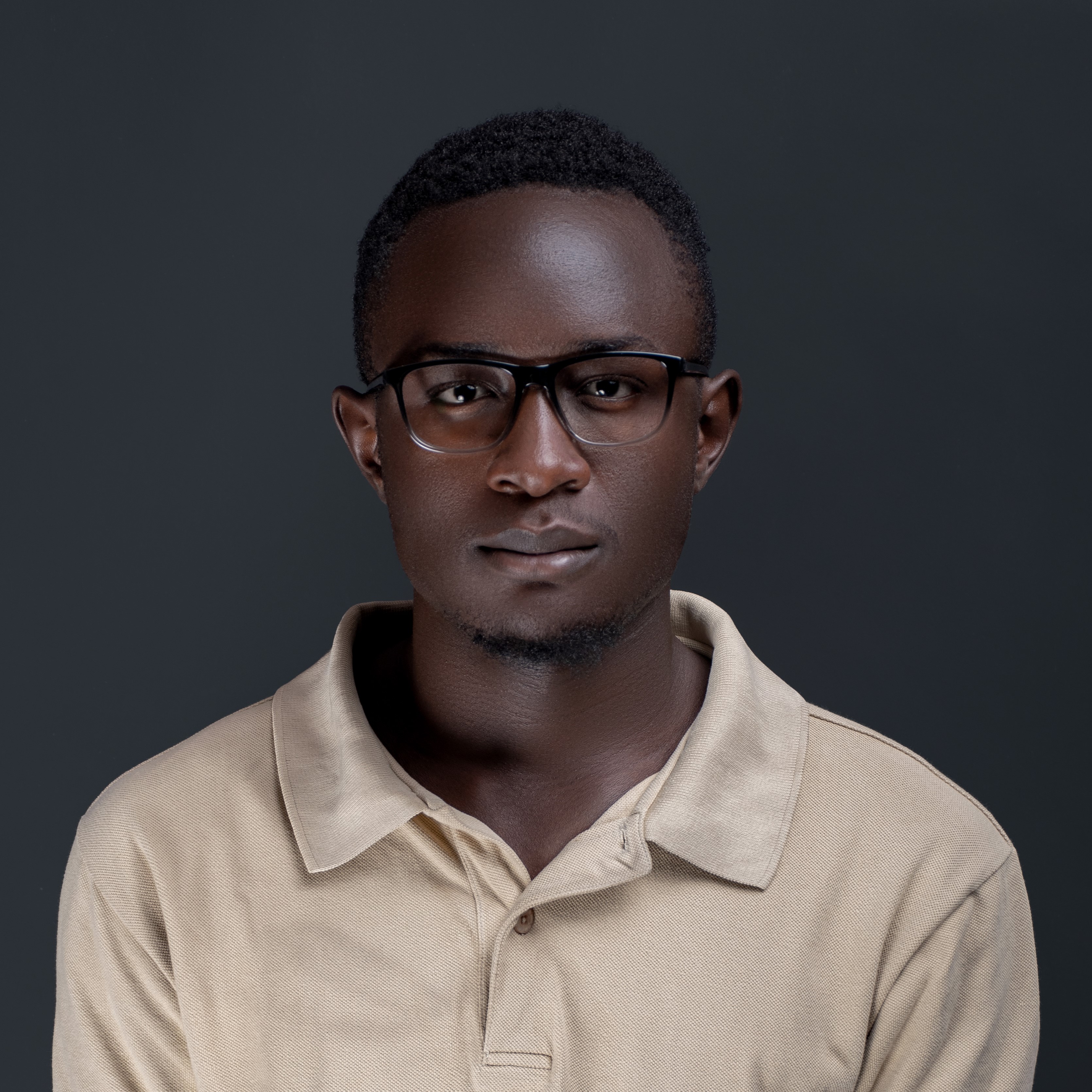

I met Mary Wanjiku, 34, in Embakasi last December. She had spent the morning baking a cake for her children and wrapping presents, yet her eyes carried a weight the festive colors could not hide. Her husband had died earlier that year, and for her, the season was not about celebration—it was about surviving the quiet that followed loss. “People tell me to smile for the kids, to be thankful,” she said. “But grief does not care about gifts or lights. It waits. It watches.”

And still society insists: be thankful. Others have it worse. At least you are alive.

This insistence is not harmless. It teaches people to hide, to swallow pain, to believe they are failing at joy. It asks the already hurting to perform for the comfort of others. It turns emotional survival into a moral test.

Joy is easier when life is stable. Celebration is lighter when your body feels safe. Gratitude flows more freely when your mind is not at war with itself. But Christmas often arrives when finances are tight, when families are fractured, when estrangement feels permanent. It arrives in hospital wards, in mourning homes, in single rooms where no one is coming.

Recent studies in Kenya show that depressive episodes spike during holiday months. A 2021 survey by the Ministry of Health found that more than 12 percent of adults reported heightened anxiety and sadness in December. Mental health resources do not increase to match this surge. Expectations multiply, but care does not deepen. We decorate symptoms instead of addressing causes.

And yet, gratitude is demanded. Gratitude, when compulsory, becomes another burden. It suggests pain is a moral failure, that joy is earned by attitude, that sadness is evidence of ingratitude rather than a response to lived reality.

Emotions are not moral achievements. They are information. What would it mean to let Christmas be emotionally honest?

I spoke with 19-year-old Kevin Mwangi in Kayole, Nairobi. He works at a local construction site and cares for his younger siblings after the death of their parents. “We put on tinsel for the children,” he said. “But when everyone else is singing, I think about them. About what they lost. About what I lost. I can’t be happy on command.”

And so people perform. They laugh harder than they feel. They attend gatherings they are not ready for. They post photos that do not match their inner lives. They force cheerfulness because sadness feels like failure in December.

But pretending does not heal. Rituals that once brought comfort now reopen wounds. You remember who should have been here, who used to be here, who will never be here again. And yet the dominant cultural script offers no space for this reality. We say, “Count your blessings,” as if that solves anything.

The pressure to perform happiness often worsens depression and anxiety. It creates a second wound: not only am I hurting, but I am hurting incorrectly.

Christmas can be emotionally unsafe. It rewards those who can participate fully and invisibilizes those who cannot. It centers family without acknowledging that family can hurt. It celebrates abundance without reckoning with scarcity.

In Diani, I met 35-year-old Felix Kangara, born with a physical disability that limits his mobility. He spends December watching tourists stroll past palm trees, wishing he could move with the same ease. Jobs, even seasonal ones, remain out of reach. “I just want to feed some chickens,” he said. “A small project, something to depend on. But no one gives me a chance. Even at Christmas, I feel invisible.”

What if we allowed Christmas to be quieter? What if people could show up as they are—unfestive, un-fixed, ungrateful—and still be seen? What if sadness were not treated as an inconvenience?

Mental health during Christmas is not about forcing joy. It is about permission. Permission to rest. Permission to decline invitations without explanation. Permission to feel grief without apology. Permission to survive the season rather than “enjoy” it.

In Nairobi, a community group called MindTheMap has spent the past two holiday seasons providing safe spaces for young people to talk about anxiety, stress, and depression. Their founder, Isaac Kamau, told me: “We see youth who feel trapped between tradition and survival. Christmas amplifies that tension. They need space, not slogans.”

We do not need more slogans in December. We need honesty. Gentler expectations. Language that does not shame pain.

And most of all, we need to remember: no one owes joy to a holiday. Christmas will pass. But the people among us—hurting, quiet, unseen—will remain. How we treat them during the loudest season of the year says more about us than any celebration ever could.

Let this year, let every year, be a season that asks less of the vulnerable and more of us. Let Christmas not be a performance, but a permission. Permission to notice. Permission to pause. Permission to be human.