Mourning Yourself: Living With Depression in Kenya

Reading Time: 2min

How do you mourn someone who is still alive? Or worse, yourself?

Growing up, we carry visions of how life will unfold. We call it hope—a quiet promise that things will make sense, that we will become the people we imagine. But what happens when life, as you know it, begins to feel like oblivion? When your days pass in a haze of routine, disconnected from your own desires, observing rather than living?

For 29-year-old Aisha Mwende from Kibera, Nairobi, the question is all too real. “Some days I wake up and wonder if I’m still me, or if I’m just going through the motions,” she says, sitting on the edge of a well-worn sofa in her mother’s single-room home. “I smile for my siblings, for my friends, but inside… inside I feel nothing.”

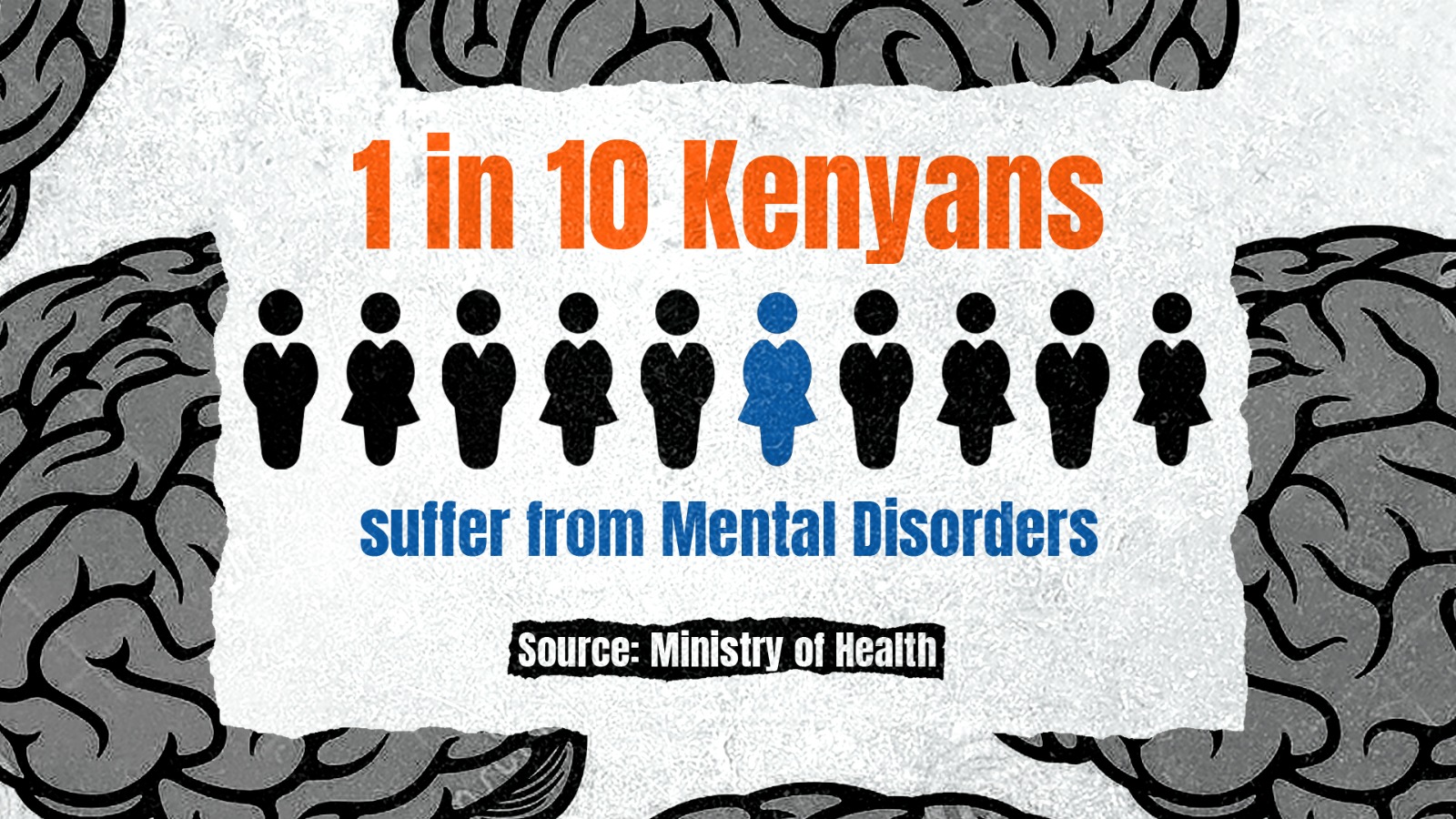

Many Kenyans live with this quiet companion called depression. According to the Ministry of Health, nearly 1.9 million adults in Kenya are estimated to experience clinical depression, yet less than 10 percent receive formal care. Among youth and young adults, rates are rising. NACADA’s 2022 report notes that substance abuse, unemployment, and social pressures exacerbate mental health struggles—showing how depression, anxiety, and hopelessness often intertwine in a vicious cycle.

Depression is not always loud. It hides in overconfidence, in high functionality, in the compulsive need to prove oneself. You show up. You perform. You survive. And yet, quietly, you are sinking. “It feels like walking underwater, even when the surface is just meters away,” Aisha explains.

The danger lies in how depression grows on you. Over time, it becomes familiar, almost loyal. It feeds on your energy, shapes your decisions, and erases fragments of the person you once were. Friends notice your change, colleagues comment, but often no one sees the full picture. For 35-year-old Felix Kangara from Diani, Kwale County, who lives with a physical disability and daily anxiety, the struggle is compounded by isolation. “Some days, I feel like I’m fading,” he admits. “I keep busy, try to help my mother, but the loneliness clings to me.”

The challenge in Kenya is structural as well as personal. Mental health resources are scarce: one psychiatrist serves roughly 500,000 people, and most services are concentrated in Nairobi, Mombasa, and Kisumu. Counties with growing populations and high unemployment—Kibera, Kwale, Kilifi, Kisumu—struggle to provide adequate care. Where services exist, stigma often prevents people from seeking help. As Dr. Isaac Kamau, a clinical psychologist in Nairobi, explains: “Many young people would rather hide their symptoms than be labeled ‘mad.’ The silence allows depression to deepen.”

Depression in Kenya often intersects with poverty, substance abuse, and social isolation. Youth leaders from Nairobi, Kilifi, Nakuru, and Kisumu recently told MindTheMap, a Nairobi-based mental health advocacy initiative, that alcohol, khat, and cannabis use were skyrocketing among young people, worsening anxiety and depression. “Young people see intoxication as social capital,” said Brian Otieno, a Kisumu youth leader. “It starts as fun and ends as dependence. And mental health is the first casualty.”

But depression is not merely a social problem; it is a profoundly human one. It erodes identity, blurs lines between survival and living, and leaves people mourning the life they imagined. For Aisha, this means nights of staring at the ceiling, reliving perceived failures. For Felix, it means a day of watching life pass by, wishing he could participate fully. For countless others across the country, it is a quiet, invisible struggle.

Healing, however, is possible. And it begins with acknowledgment. Self-mourning—the grief for the person depression has taken—is not weakness; it is the first step in reclaiming your life. For many Kenyans, peer networks, community-based organizations, and mental health advocates offer lifelines. Groups like MindTheMap, BasicNeeds Kenya, and the Kenya Red Cross have begun to provide counselling, training, and peer support. These efforts are small but meaningful: they transform isolation into connection, despair into action.

True healing also requires systemic change. Schools, workplaces, and county governments must expand mental health support, integrate services, and normalize care-seeking. Training for teachers, health workers, and community leaders is vital. Policies exist—the Mental Health Act of 2018 is a framework—but implementation lags. Without structural support, the burden remains personal, heavy, and ongoing.

Walking away from depression does not mean forgetting the pain or denying the struggle. It means leaving behind the shadows that shaped you, reclaiming your energy, and discovering who you are beyond illness. It is in small acts: a morning routine that centers you, a phone call to a friend, a walk in the sun, a therapy session, a quiet moment of reflection. It is the reclamation of the self that depression attempted to erase.

Aisha sums it up: “I am learning to be kind to the person I am now, even if she is not the one I imagined. I mourn the me I lost, but I am trying to meet the me I still have.”

In Kenya, where mental health remains stigmatized and underfunded, mourning oneself is a quiet revolution. It is an acknowledgment of pain, a confrontation with isolation, and a declaration that life, though altered, can be reclaimed. It is not a journey for the faint-hearted, but it is one worth taking.

Because in the end, leaving depression behind is not giving up. It is survival. It is reclamation. It is living. And perhaps, in walking away from the darkness, we finally meet ourselves again.