The Purple Profile Picture Isn’t Enough

Reading Time: 3min

In 2025, we are more than informed. We know mental health is no longer a whisper in the dark. It cripples, detaches, and can drive a person to the unthinkable.

The purple profile picture on social media alludes to solidarity, but what does it mean when the menace is heartbreakingly real, hidden behind stoic faces and unspoken pain?

A Crisis in Plain Sight

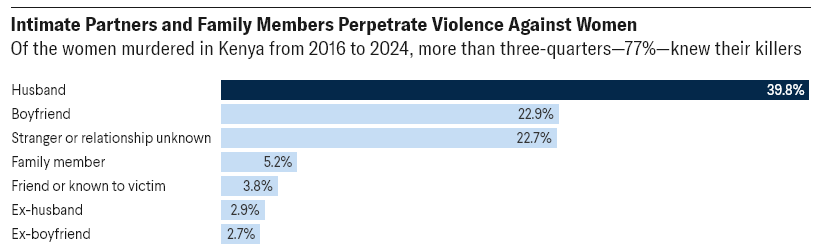

Let us begin with the numbers. Globally, roughly 85,000 women and girls were intentionally killed in 2023. That means about 60 percent of these murders were carried out by intimate partners or family members. Africa bore the highest burden that year, with an estimated 21,700 victims in intimate partner or family member femicide.

These are not just statistics. Each number represents a life lost, a family scarred, and communities destabilized. The unrelenting wave of gender based violence and femicide in Africa is inseparable from the mental health crisis. It affects both survivors, and the men who perpetrate or are affected by these crimes.

A Broken Infrastructure

Part of the problem, of course, is not just social stigma. It is structural neglect. Africa’s mental health systems are severely under resourced. According to the World Health Organization, nearly 150 million Africans are living with mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, yet services remain fragmented and inaccessible. On average, Africa has just one mental health worker per 100,000 people. This compares to the global average of nine. Moreover, governments have underinvested dramatically.

Femicide and Fragmented Healing

When we talk about femicide, the gender related killing of women and girls, we must also talk about what it does to the mental health of survivors’ families, witnesses, and communities. Each life lost is a traumatic rupture, a constant reminder of the cost of patriarchy left unchecked. For communities grappling with grief, rage, and survivor guilt, the mental health toll is profound.

And still, accountability lags. In South Africa, fewer than one in five intimate partner femicide cases result in convictions. This impunity is not benign. It reinforces trauma, isolation, and despair, especially when the promise of justice feels out of reach.

Vulnerability Is Not Weakness

If we are to confront this crisis, we need more than purple avatars and hashtags. We need a social revolution, one that rewrites what strength means for men, and rethinks how we build mental health systems in Africa.

We must integrate mental health into gender based violence response. When femicide happens, mental health support must be part of healing for survivors, for families, and for men too. Perpetrators and their kin often need psychological intervention, not just punishment.

We must invest in mental health infrastructure. Governments need to dramatically increase funding, expand workforce capacity, and decentralize care. Mental health should not be a luxury. It is a public health necessity.

We must strengthen data collection. We cannot fight what we cannot measure. Better data on intimate partner violence and femicide is needed to design effective interventions.

Every purple profile picture is a reminder. But if we truly want change, we must go beyond symbolism. We must break the silence, dismantle stigma, and build systems of care that reflect the real, messy lives of African men and women. Because vulnerability is not weakness. And healing begins when we dare to speak.