PWDs in Kwale Decry Lost Opportunities

Reading Time: 4min

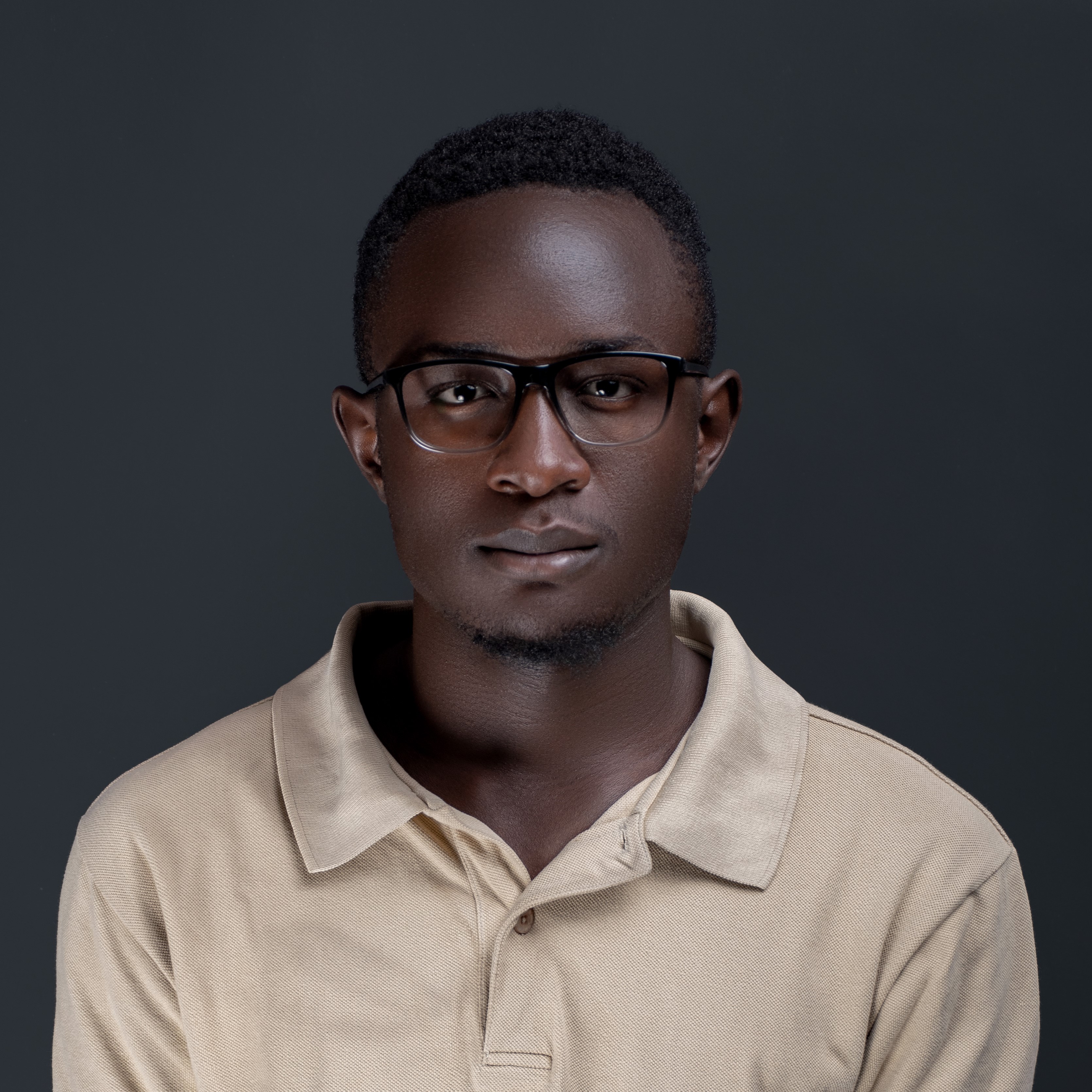

Every morning in Diani Beach, as tourists stroll past luxury hotels and the sway of palm trees, 35-year-old Felix Kangara settles outside his family’s modest rental house. From here, he watches the effortless pace of people heading to work—the movements he wishes he could make on his own.

Born with a physical disability that limits his mobility, Felix often relies on his 63-year-old mother to carry him around their neighbourhood. It is a bond forged by necessity, but one that now weighs heavily on both of them.

For the past decade, Felix has tried everything to find work. He has submitted applications to hotels, shops, and local projects—anything promising a steady income. Every time, the outcome has been the same: silence or polite rejection.

“I have knocked on every door in Diani,” he says, forcing a smile that doesn’t quite hide the fatigue. “People say there are jobs, but not for someone like me. If I had some capital to start poultry farming, I would at least depend on myself.”

Felix’s frustration reflects a wider struggle for persons with disabilities (PWDs) across Kwale County. Despite economic growth, new hotels, expanding farms, and busy construction sites, many PWDs say opportunities remain out of reach.

Kenya’s Employment Act and the Persons with Disabilities Act promise equal opportunities and require at least five percent of public service jobs to be held by PWDs. On the ground, however, disability rights groups say these laws rarely translate into real employment.

During this year’s World Disability Day in Kinango, Kwale County, advocates were blunt: many challenges remain unresolved.

“Kwale has booming hotels, quarries, farms, and construction sites,” said disability rights coordinator Shiela Wasu. “Yet very few PWDs are on the payroll. Employers assume it will cost too much to accommodate us, or they underestimate our abilities.”

Some workplaces hold interviews in buildings with steep entrances and no ramps. Others offer no sign language support or post vacancies online in ways inaccessible to visually impaired applicants. County departments rarely follow through with disability inclusion audits.

For Felix, the idea of poultry farming is not a lofty business dream—it is a path to independence.

“I know I can do it,” he says. “I can feed the chickens and keep records. My mother can supervise. But without even a small amount of capital, the idea just stays in my head.”

Entrepreneurship could be a lifeline, advocates say. Yet accessing county loans or national funds often demands mobility, formal paperwork, guarantors, or digital literacy—barriers that shut out many aspiring PWD entrepreneurs. Even county efforts to award more tenders to local businesses have failed to reach them. Complex documentation, lack of training, and subtle bias from procurement officers leave many excluded.

For Margaret Kangara, Felix’s mother, each day is a mix of support and worry. She loves caring for her son, but she knows she is aging.

“I fear for his future,” she admits. “If he had a small project, even just chickens, he would not depend on me. That is all a mother wants—to see her child stand on his own.”

Kwale Governor Fatuma Achani, responding to PWD advocates’ concerns, urged caregivers to help their children acquire training and skills aligned with available opportunities.

“We have minimum requirements, just like any employer,” Achani said. “Caregivers and parents should help their children get an education and set up companies so they can qualify for County tenders.”

As evening light softens over Diani’s white sands, Felix leans back in his chair, watching children race along the sandy path outside. For a moment, he smiles, then the expression fades.

“One day,” he says quietly, “I want people to know that disability is not inability. I just need a chance or a small start.”

In Kwale, that chance remains distant for many like him. The hope is steady but strained, as opportunities continue to slip away.