Building Villages That Heal: How Kenyan Communities Are Fighting Mental Health Stigma

Reading Time: 2min

In the heart of Kenya, a quiet revolution is unfolding. For decades, mental health was spoken of in whispers, tucked behind closed doors, often misunderstood as a curse, demonic possession, or personal weakness. Families feared judgment. Neighbours feared contamination. And the people most in need—those battling depression, psychosis, or anxiety—were left to suffer in silence.

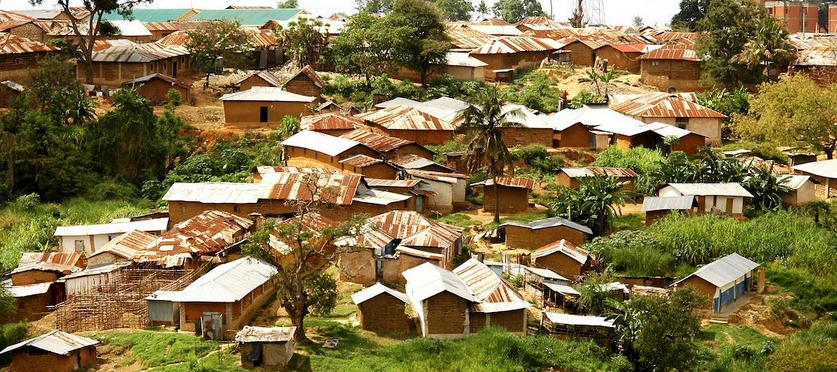

Yet across the country, a new story is emerging, one where community itself becomes medicine. In Mombasa, Kilifi, Kisumu, and Nairobi, grassroots efforts are quietly dismantling stigma, one conversation, one support group, one life at a time.

The weight of stigma in Kenya is heavy. Traditional beliefs have long linked mental health conditions to witchcraft or supernatural punishment. The result is discrimination: individuals are labeled “mad,” “possessed,” or “weak,” often perceived as dangerous, even though evidence shows they are far more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence. Families sometimes hide their loved ones—locked away, restrained, or abandoned—out of fear of societal backlash.

Consider Charo Mwangi from Kilifi County. At 35, he was confined in chains by his own family for nearly four years after experiencing untreated psychosis. His story is no longer unique in Kenyan headlines, but for the people living it, each day is a quiet crisis. Fear keeps families silent, and silence allows mental health conditions to worsen. The Ministry of Health estimates that around one in four Kenyan youths experience depression or anxiety symptoms, yet most remain untreated.

Government intervention alone cannot shoulder this crisis. Mental health receives just 0.01% of the national health budget, and Kenya has fewer than 100 psychiatrists and about 500 psychiatric nurses for a population of over 50 million. Rural communities feel this acutely: even those willing to seek help find clinics far away, understaffed, or inaccessible.

Within this challenge, however, lies hope. The solution often begins at the community level. Recognizing that formal systems are overstretched, initiatives are harnessing local human resources. Community health volunteers, faith leaders, and trained traditional healers are becoming the first line of defense. These are trusted faces, already embedded in neighborhoods, uniquely positioned to identify and support those in need.

In Kilifi, the Difu Simo initiative—Swahili for “Breaking Free”—is teaching communities to challenge myths around mental health. During a workshop in Malindi last year, 28-year-old student Amina Hassan shared how she had been told her panic attacks were caused by spirits. “I felt like I was losing my mind and my family’s respect,” she said. Through Difu Simo, she learned about anxiety, grounding techniques, and local counseling resources. Today, Amina volunteers with the program, leading discussions with other young people who had nowhere to turn.

Basic Needs Basic Rights Kenya (BNBR) has also transformed lives. They were instrumental in Charo’s release, providing a proper diagnosis, treatment, and counseling that helped rebuild his family’s trust. Similarly, Festus Otieno, a former university student in Kisumu, was struggling with depression and suicidal thoughts. Through Cheshire Disability Services Kenya (CDSK), he received business skills training and started a small soap-making enterprise. The income allowed him to afford medication and regain independence, and he now runs a peer support group for other young people facing mental health challenges.

These grassroots efforts are reshaping understanding. Safe spaces allow silence to break, and isolation to fade. Young people are discovering that they are not alone. Communities are learning to respond with empathy rather than fear.

Education is key. Programs confront harmful myths directly:

Myth: Mental illness is caused by witchcraft or curses.

Fact: Mental health conditions have biological and psychological causes and are treatable.Myth: People with mental disorders are dangerous.

Fact: They are more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence.Myth: Seeking help is a weakness.

Fact: Seeking professional care is a sign of strength, just like treating a physical ailment.

Across Nairobi’s informal settlements, similar conversations are happening. In Kayole, youth leader Kevin Mwangi hosts weekly gatherings where young people talk about anxiety, depression, and the pressure to perform academically while supporting families. “Many thought they were alone, that no one understood,” Kevin says. “Once we start talking, they realize they are part of a network, a community that can hold them.”

In Mombasa, faith leaders are joining the movement. Reverend Paul Ndolo, who runs a church-based counseling program in Likoni, explains: “We teach that seeking mental health support is not a rejection of faith. It is part of caring for the body and mind God gave us.”

The results are profound. Peer groups, workshops, and locally-led initiatives are building villages that heal. People like Charo, Festus, Amina, and Kevin show that recovery is possible, that community care can fill gaps left by underfunded systems, and that stigma can be dismantled one conversation at a time.

Yet, the journey is far from over. Kenya still struggles with underfunded mental health services, deeply ingrained stigma, and insufficient professional support. Policy is crucial, but the most transformative healing often begins with a neighbor’s empathy, a peer group’s encouragement, and a village’s willingness to embrace, rather than ostracize, those who are struggling.

This is how stigma is broken: not by a single hero, not by hospitals or policy alone, but by entire communities choosing to become sanctuaries of support. Across the country—from Kilifi’s coast to Nairobi’s informal settlements, to Kisumu’s lakeside neighborhoods—Kenya is learning to build villages that heal. And in these villages, no one has to suffer alone.