They Raise Children While the Internet Hurls Stones

Reading Time: 7min

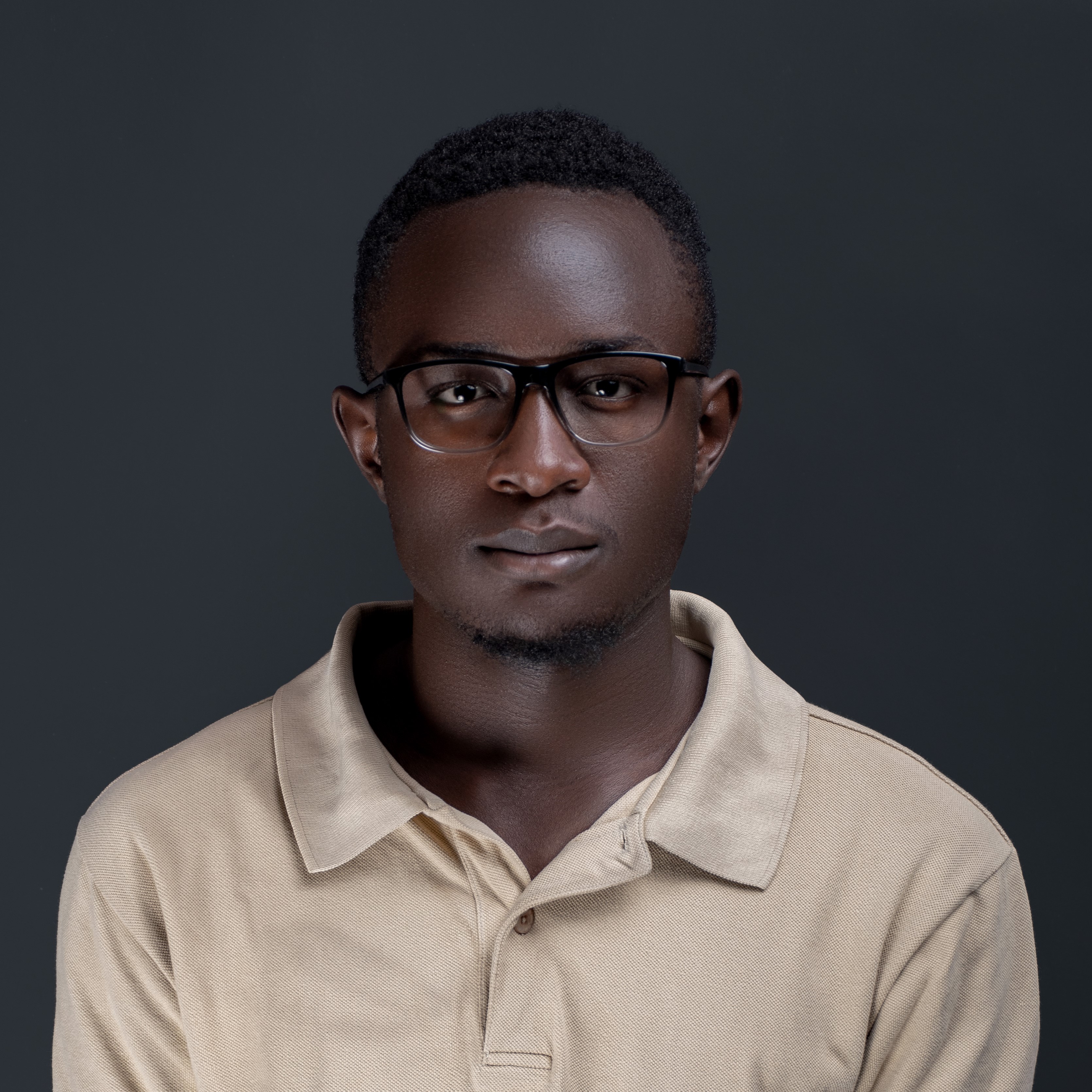

Young Motherhood, Masculinity Wars, and the Quiet Resilience of Women Across Nairobi and Kenya’s Coast

By the time Shirley Achieng wakes up in Kibera at 5.30am, the insults have already arrived. They sit quietly on her phone screen—Instagram comments, forwarded screenshots from friends, WhatsApp statuses dissecting women like her. The language is familiar now. “Used.” “Baggage.” “Single mothers are red flags.” Some are memes. Others are threads written by men who have never met her, never paid a clinic bill, never carried a child on their back through mud.

Shirley is 23. Her son is three.

“I don’t even argue anymore,” she says, standing outside her one-room house near Lindi. “You argue, they enjoy it. You stay quiet, they say you’ve accepted your shame.”

She bathes her son using water fetched the previous night, prepares him for daycare, and leaves for her casual job in Industrial Area. What the comments do not show is this routine: the receipts, the fatigue, the discipline of survival. Online, however, Shirley is a caricature—flattened into a stereotype that travels faster than truth.

Across Nairobi and along Kenya’s coast, young mothers—particularly those who had children outside marriage—are finding themselves at the center of a loud, often cruel digital economy. Social media platforms have become battlegrounds where morality, masculinity, and resentment collide, and where women’s lives are reduced to cautionary tales for male audiences.

This is not incidental. It is curated.

The New Public Square

In Kileleshwa, where cafés open early and security guards outnumber children in some apartment blocks, Laura Wanjiru scrolls through Twitter while waiting for her Uber. She is 29, works in communications, and raises a six-year-old daughter.

“I live a normal life,” she says. “School runs. Deadlines. Rent. But online, I’m a problem that needs to be warned against.”

The tone differs slightly from Kibera. The insults are dressed up as “analysis” and “dating advice.” Long threads explain why men should avoid women like her. Podcasts debate her “choices.” Viral clips frame single mothers as evidence of societal collapse.

“It’s intellectualised contempt,” Laura says. “They pretend it’s data.”

What links Kibera and Kileleshwa is not income but exposure. Smartphones have collapsed geography. A comment written in a bedsitter in Kasarani or a cybercafé in South B can land, within seconds, in the emotional space of a woman commuting on Ngong Road or queuing at Mbagathi Hospital.

The cruelty is rarely spontaneous. Many of the most aggressive narratives originate from pages and accounts explicitly built around “male self-improvement,” “high-value masculinity,” or “dating truths.” Their engagement thrives on outrage. Young mothers are easy targets: visible, vulnerable, and already burdened by cultural judgment.

Masculinity as Performance

One such page is run by Brian Mwangi, 28, who lives in Ruaka and describes himself online as a “truth teller.” His content regularly features screenshots of women’s posts, often accompanied by captions mocking their life choices. Single mothers are a recurring theme.

Reached by phone, Brian does not deny his intent.

“I post what people think but are afraid to say,” he says. “Men are tired.”

Brian has no children in his care, but he does have a child born out of a relationship that ended badly. He does not see his son often. Asked whether this history informs his content, he pauses.

“Pain makes you honest,” he finally says.

What Brian calls honesty, the women targeted by his page experience as punishment. Screenshots circulate without consent. Names are sometimes visible. Comment sections fill quickly.

“I stopped posting my face,” Shirley says. “You don’t know who is watching.”

The irony is that many of these pages borrow the language of responsibility while absolving themselves of it. Fatherhood is rarely discussed with equal ferocity. The absence of men from childcare narratives is treated as natural; the presence of women raising children alone is framed as failure.

Sociologist Dr. Mercy Mutua, who researches digital gender dynamics at the University of Nairobi, describes this as “selective morality.”

“These spaces are not about ethics,” she says. “They are about control. Masculinity is being performed for other men, and women’s lives are the stage.”

The Weight of the Stereotype

In Kayole, 21-year-old Faith Muthoni sits outside her mother’s house shelling peas. She dropped out of college after giving birth last year. The father of her child sends money occasionally.

“Sometimes I read those posts and I believe them,” she says quietly. “That I ruined my life.”

The psychological toll is cumulative. Mental health practitioners report rising cases of anxiety and depression among young mothers, particularly those active on social media.

At a counselling center in Umoja, therapist Josephine Odhiambo says many clients present with shame rather than trauma.

“They feel they must apologise for existing,” she explains. “Online narratives validate their worst fears.”

Yet offline, these same women are holding families together. They are primary caregivers, income earners, emotional anchors. The contradiction is stark.

In Kibera, Shirley is part of a small savings group run by other young mothers. They contribute Sh200 weekly. The money helps with school fees, clinic visits, emergencies.

“That’s where I feel human,” she says. “Not online.”

The Coast: A Different Geography, the Same Judgment

In Kwale County, the insults arrive slower but cut just as deep.

Amina Said, 26, lives in Msambweni and sells cooked cassava by the roadside. She had her first child at 19. The father left for Mombasa and never returned.

“In the village, they don’t need the internet to shame you,” she says. “They look at you.”

But WhatsApp has changed the scale. Screenshots of Facebook posts circulate in local groups. Sermons are forwarded. Moral policing becomes communal.

“When a man leaves, people say it’s normal,” Amina says. “When a woman stays, they say she is cursed.”

Still, Amina has built a life. Her stall feeds her two children. She recently joined a women’s cooperative that helped her buy a second cooking pot.

“I am not waiting to be saved,” she says.

In Malindi, the dynamics are complicated further by tourism and economic precarity. Young mothers are often assumed to be involved with foreign men, regardless of reality.

Halima Juma, 31, works at a guesthouse in Majengo. She has one child.

“People assume your story before you speak,” she says. “They don’t ask.”

Online, coastal women face an additional layer of racialised and moral judgment, particularly when their livelihoods intersect with hospitality or informal trade.

Sidebar: Five Voices, Five Places

1. Shirley Achieng, 23 – Kibera, Nairobi

Struggle: Online harassment, unstable income

Small victory: Enrolled her son in daycare using savings group funds

“I learned to mute comments. Silence is survival.”

2. Laura Wanjiru, 29 – Kileleshwa, Nairobi

Struggle: Professional stigma, dating discrimination

Small victory: Secured a promotion while raising a child alone

“They underestimate how organised you become when you have no backup.”

3. Faith Muthoni, 21 – Kayole, Nairobi

Struggle: Dropping out of college, self-doubt

Small victory: Registered to return to school part-time

“I am not done.”

4. Amina Said, 26 – Msambweni, Kwale

Struggle: Single income, village stigma

Small victory: Expanded her food stall

“My children eat. That is my response.”

5. Halima Juma, 31 – Malindi, Kilifi

Struggle: Stereotyping linked to tourism work

Small victory: Started saving to open a small shop

“They talk. I plan.”

Quiet Resistance

What unites these women is not victimhood but adaptation. They curate their online presence, form offline networks, and redefine success away from approval.

Community organisations are beginning to respond. In parts of Nairobi and the coast, youth-led mental health initiatives and women’s collectives are offering counselling, legal advice, and digital safety training.

“These women don’t need pity,” Dr. Mutua says. “They need narrative space.”

The internet, after all, reflects power. Who gets to speak loudly. Who gets believed. Who gets reduced to a warning sign.

As Kenya’s digital culture matures, these questions will not disappear. For now, young mothers continue to raise children while being publicly debated by strangers.

In Kibera, Shirley locks her door at night, scrolls past another thread, and switches off her phone.

“Tomorrow,” she says, “my child still needs breakfast.”

And that, more than any comment section, remains the truth.